AR-1 | Simple low wing-loading RC airplane

For a long time, I wanted to create an airplane inspired by the design of a radio-controlled pylon racer. These aircraft are essentially overpowered gliders that are built to sustain large G-forces. Their appeal lies in using a highly energy-efficient platform that’s modified for high speed. This can result in an overpowered aircraft with low wing loading that is capable of abrupt maneuvers. Plus, I find the aesthetic pleasing: a simple tube-like fuselage with a straight wing and tail. Many of these models use composite materials for the fuselage and wings, which leads to efficient airframes at the cost of a complex manufacturing process.

On the other side of the spectrum, there are designs like the GWS Slow Stick. The design is very simple as it’s just a stick with supports that hold the aerodynamic surfaces, electronics, and motor. While this exposed setup creates a lot of drag, it’s easy to build and maintain. The simplicity results in a lightweight airframe with low wing-loading. As the name implies however, the plane is designed for slow fligh so the larger drag caused by the fuselage isn’t as important.

Both of these approaches are interesting in their own ways. The pylon racer is fast but complex, while the stick design is slow and simple. Since both have their appeal, it’s a good challenge to find a middle ground that offers both: ease of construction and relatively low drag. This is where scale plays an important role. Since we’re dealing with small radio-controlled models and won’t be reaching very high speeds, we can safely expect to operate at low Reynolds numbers. Specifically, in the range of 30,000 to 100,000. In this range, studies have shown that airfoils for low Reynolds numbers can be simple yet effective. A curved flat plate works well in these conditions:

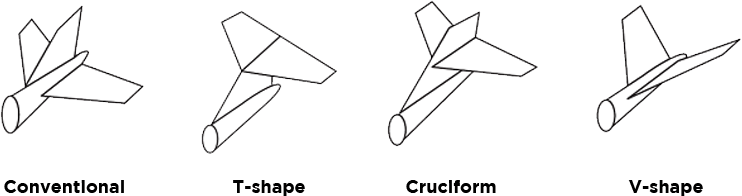

With this in mind, we can simplify our wing to a flat 2D sheet with some camber. Similarly, the tail surfaces can be thin flat plates with rounded edges. To further simplify the aircraft, we can opt for a V-tail wherein the angle of the V determines how the effective stabilization along the vertical and horizontal axes.

A V-tail has the added benefit of lower mechanical complexity. Each side only requires one movable flap, controlled by an actuator. Since both sides are symmetrical, the mechanism is identical for each using the same servos and control linkages. The only drawback is the mixing required for pitch and yaw control, as both sides must move together to achieve control. However, this can be easily handled electronically with programmable servo motion.

We’ll shall reduce the fuselage to a stick with the components attached as per the slow-stick design. By placing these components close together, we can also reduce their combined drag. For example, it’s easier to push a box with many boxes behind it through the air than pushing each box separately through undisturbed air. There are other drag-reducing effects to consider as well, such as the corrugated airfoil of a dragonfly wing:

Despite its non-streamlined shape, the air flows smoothly over the corrugated wing.

Similarly, a properly tailored non-streamlined shape can still have relatively low drag at low Reynolds numbers if airflow conditions are stable. In the case of a fuselage, this holds true since it’s usually aligned with the airflow. Both the angle of attack and sideslip angle remain small.

With all of this in mind, it took me about a day to build a model airplane. The flying surfaces were made from Depron foam that was reinforced with carbon fiber strips and fiber-reinforced kite tape. The fuselage was a 5mm pultruded carbon fiber tube. The tail was controlled by two 3g analog servos, and I used a 1306 brushless motor with a 5030 propeller for power. To keep things simple, only the tail was actuated so roll control relied on the wing’s dihedral angle. The wing was split into two sections and joined at an acute angle of about 10 degrees. The energy source was a 400mAh 2S LiPo battery that powered the servos, a 6-channel receiver, and a 6A brushless ESC. Here’s the result:

A few photos of the airplane on the beach

The total weight of the model is about 180 grams, with a wingspan of 70 cm and a root chord of 20 cm. The wing had a tapered planform with rounded edges. These tips prevent the wing from digging into the ground during landings and improves lift distribution across the wing as it has a small taper ratio. A simple cambered plate with a rounded leading edge and a triangular trailing edge was used for the airfoil.

Flight of the airplane in a calm beach breeze

Overall, this was a very satisfying project. The airplane flew well—not super fast, but not slow either. The controls weren’t very aggressive, but with V-tail control and dihedral, the roll response was sufficient for calm flight. Pitch control was quite responsive. The low wing loading allowed for tight turns at full throttle. While its gliding performance wasn’t extraordinary, I’d estimate a glide ratio of around 4:1 when trimmed correctly in calm conditions. Overall, this was a great result given how easy the plane was to build. This platform offers plenty of potential for trying out other concepts in the future as it’s both simple and highly modifiable.