Review | Sensor fusion algorithm for an IMU based on a quaternion

Introduction

In the process of developing an autonomous tracked robot, it was deemed critical to create a system to track the vehicle’s heading. This involved combining information from an inertial measurement unit (IMU) into a useful heading estimate. The process of combining this information is called sensor fusion, which can be accomplished through a properly designed algorithm. At the core of the algorithm is a mechanism to encode the sensor’s orientation. This can be done using rotation matrices or quaternions. In this case, using a quaternion is preferable because it is mathematically simpler than a rotation matrix. It does not require extensive use of sine and cosine functions, and all of the heading can be encoded using just four numbers. This simplicity makes it well-suited for an algorithm that needs to be executed continuously, as it is computationally inexpensive to repeat any calculations.

A separate vector and quaternion library was developed to handle the mathematics involved in manipulating quaternions and any vectors that the quaternions would act upon. These data types were then used by the sensor fusion algorithm to perform heading computations. The fusion algorithm was extensively tested using an MPU-6050 inertial measurement unit. Another library was specifically developed to interface the MPU-6050 with an Arduino. Thus, the sensor fusion algorithm depended on two custom libraries to create a functioning system. We can consider this system to be a filter that acts on the raw data from the sensor. Therefore, the sensor fusion algorithm can also be referred to as an IMU filter, as it filters the information from the inertial measurement unit.

Note: The auxiliary libraries developed for the IMU filter can be found here:

Initial PID-Based Filter

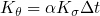

The initial form of the fusion algorithm was based on existing IMU filters. It was a modified version of the Mahony filter that replaces the PI controller with something akin to a second-order low-pass filter. The proportional term was removed, and the integral term was forced to decay to dampen the system. For more information on the Mahony filter, see these references:

The correction steps for each filter are shown below:

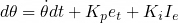

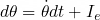

- Mahony filter: In this algorithm, the heading error is directly used to determine the heading correction. The error in heading is also integrated, and the result is included in the correction for the heading. As a result, the system behaves like a first-order low-pass filter, with a small amount of rebound due to the integral term winding up. However, because of the existence of a proportional term in the heading correction, the system responds immediately to the existence of any error. This rapid response reduces the filter’s ability to suppress noise.

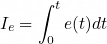

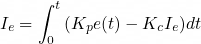

- Modified Mahony filter: The steps used by the custom filter altered the value being integrated. The integral now depended on its current value, causing it to behave like a first-order low-pass filter with respect to the heading error. This integral was then used to determine the actual heading. As a result, the heading responded like a second-order low-pass filter with respect to the heading error, as it now depended on a variable that had a first-order response.

The behavior of the modified filter is analogous to a spring-mass system. (Kp) (stiffness) and (Kc) (damping) are related by the damping ratio (Q), which is held constant. This allows the filter’s behavior to be controlled via a single parameter. The filter then uses a quaternion to encode rotations, making it easy to perform coordinate transformations, including:

- Transforming a vector from the local frame to the global frame (and vice versa)

- Obtaining unit vectors for the X, Y, and Z axes in either the local or global frame.

Since a 6-axis IMU has no absolute reference for heading, a function was included to rotate the orientation estimate about the yaw axis. Basic vector operations were included to easily implement a heading correction algorithm if an additional sensor (such as a magnetometer or another absolute heading sensor) is available.

Updated Kalman-like Filter

The sensor fusion algorithm was eventually rewritten with a completely different approach. Instead of developing an arbitrary system that mimicked a mass attached to a spring, it was more effective to consider the statistical noise of the gyroscope and accelerometer. This approach is taken by the analytically derived Kalman filter. In particular, I drew inspiration from the implementation of a 1D Kalman filter for Arduino.

Heading Estimate:

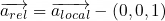

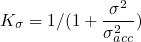

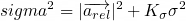

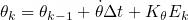

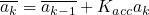

The updated algorithm used a Kalman-like filter to check the whether the acceleration was within a specific deviation from (0,0,1)g. If the acceleration was within this band, it will strongly correct the orientation. However, if the acceleration lied outside this band, it would have little effect on the orientation. To this end, the deviation from vertical was used to update the variance and Kalman gain:

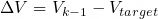

The Kalman gain is then scaled by a delay parameter and used to correct the attitude. This scaling allowed the filter to act like a first-order low-pass filter, smoothing the acceleration at the cost of a slower response:

This approach of using the magnitude of acceleration to known when to correct the heading proved very effective. It ensured the heading would not be disturbed by prolonged accelerations. The heading was only corrected when the accelerometer was within an acceptable deadband, which occurred when the accelerometer was at rest or in constant linear motion. This is a significant improvement over the initial version of the filter, which relied on an arbitrary spring-mass system to combine the accelerometer and gyroscope readings. In that case, the accelerometer would always correct the heading, regardless of whether it was accurate.

Velocity Estimate:

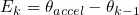

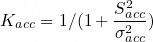

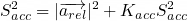

The library could integrate acceleration to obtain an estimate of velocity. This was accomplished by using a set of Kalman-like filters similar to the one shown above. The acceleration was checked against a rest condition of (0,0,0)g, and any deviations within a specified uncertainty band are suppressed. This eliminated much of the bias due to gravity or miscalibration:

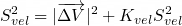

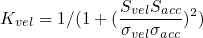

Afterward, the deviation of the velocity (relative to a known target velocity), along with the variance of the acceleration, was used to determine the Kalman gain for the velocity. This relationship caused small velocity changes or small accelerations to reduce the gain, forcing the velocity to match the target velocity:

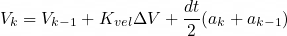

The velocity was then updated using the trapezoidal rule to integrate the filtered acceleration:

This approach led to a fairly decent estimation of velocity over short periods. The sensor would need to rapidly accelerate and then decelerate to provide an accurate reading. If the acceleration was prolonged, or if it only occurred in one direction without reversing, the output of this algorithm would rapidly decay to the established target value. Therefore, the algorithm was only well-suited for short-term disturbances rather than long-term velocity readings.

Conclusions

The IMU filter was a challenging project. It required the development of additional libraries which were projects in their own right. Furthermore, creating a robust algorithm that could accurately determine heading, without being distorted by unnecessary noise, required careful analysis of the accelerometer readings to discern when to utilize its data. This complexity was especially pronounced when attempting to convert the accelerometer values into useful estimates of velocity and position. Achieving a stable reading of velocity was particularly difficult, as directly integrating acceleration led to tremendeous instability. Consequently, any algorithm handling the integration of acceleration had to suppress any deviations in average velocity, while at the same time remaining responsive to sudden changes in acceleration.

Ultimately, the Kalman-like system that was devised may not have been the best algorithm for obtaining velocity, but it worked, and it was straightforward. It became clear that there are limitations to what an algorithm can achieve if the sensor was not very accurate. This was indeed the case with the MPU-6050, as it is a mass produced and inexpensive sensor. If a more advanced IMU were used with the filter, it is likely that the velocity estimates would be significantly better. Despite the limitations inherent in the sensors, there are also entirely different approaches to estimating velocity and orientation. For example, neural networks can be employed to provide great estimates based on precise analysis of large datasets correlated with known displacements.

See: Robust Double Integration - RIDI

It’s possible to use large datasets to train a fusion algorithm.

GitHub Repository

The filter library can be downloaded directly from the arduino library catalog. It is also available from its gitHub repository at the following link: imuFilter